In 1999, the Detroit News published Home Sweet Home: Memories of Tiger Stadium, a book containing some wonderful photos from the newspaper's archives. Check out this one of Detroit's Recreation Park on page 15 (more about that park here):

... and this nice action shot on page 19:

Another great photo is found on page 25:

Its caption reads:

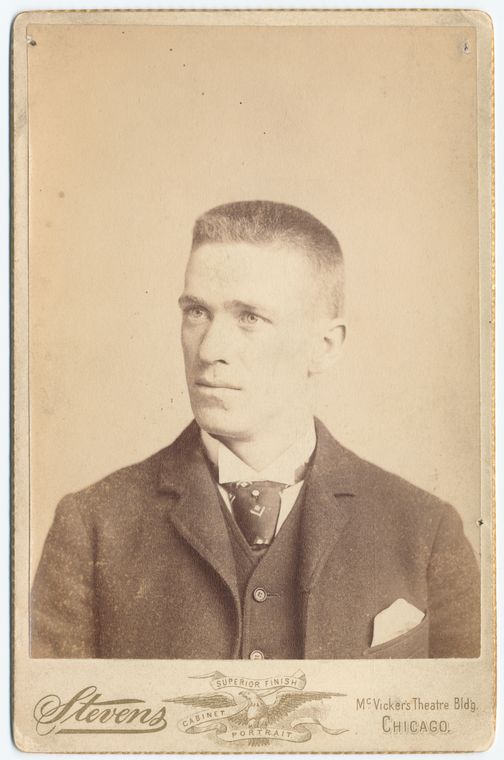

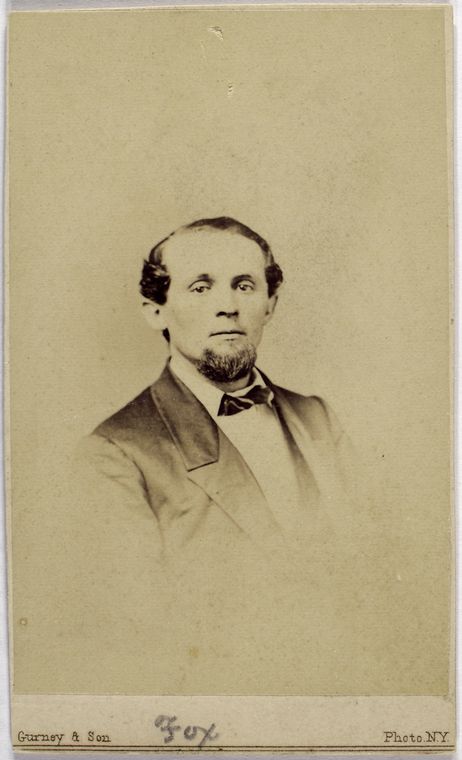

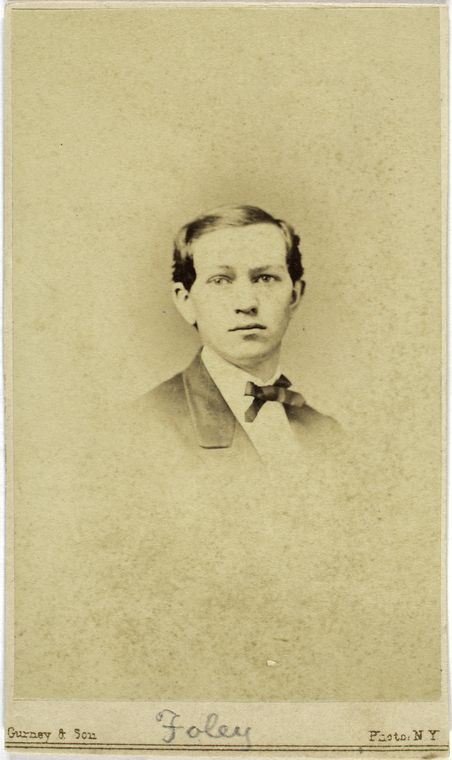

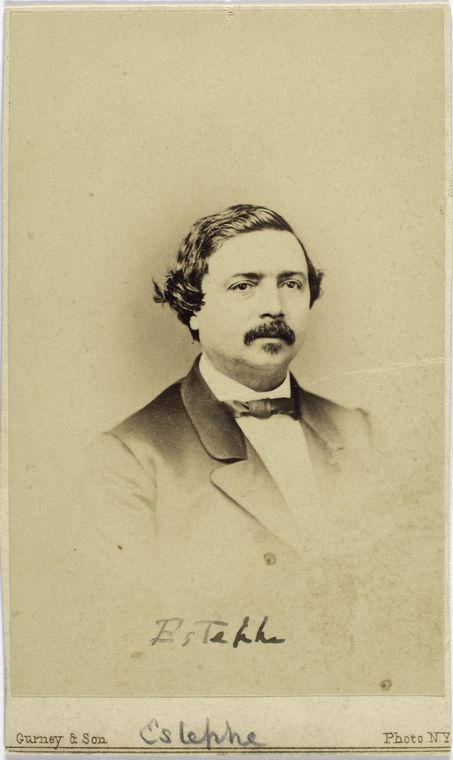

Ty Cobb was safe at home in this close play at the plate, sliding deftly under the tag of Boston catcher Lou Criger in a game at Bennett Park.It's a marvelous photo, but I've got a problem with the caption. I agree that the catcher is Lou Criger, a fairly distinctive looking fellow with light brown (or red?) hair, a thin build, and a somewhat gaunt face. Here are a few other photos of the longtime American League catcher:

Chicago Daily News negatives collection, SDN-001462. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, [LOT 13163-17, no. 43]

There's really no question that the catcher is Criger, but he's certainly not wearing a Boston uniform. Take a good look at this detail:

There is clearly a patch on Criger's left shoulder. In fact, it's a Fleur-de-lis. The same marking adorns Criger's cap, which he tossed behind him and is seen on the ground just beyond the umpire's left leg. The decorative symbol has long been associated with the city of St. Louis and was used at various times on St. Louis Browns uniforms. Indeed, Criger's uniform and cap are consistent with the club's outfit of 1908 and 1909. Since Criger's only season with the club was 1909, we can be pretty certain that was the year the photo was shot.

So while the caption states that the photo is of Criger with Boston in 1904, it's actually of Criger with the Browns, five years later.

As for the location, it is most certainly Bennett Park in Detroit. Not only are the Tigers wearing their home whites, but the roof of the stands in the background matches that seen in this large panoramic photo from the Library of Congress:

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-123165 DLC]

Note also that the two light "patches" on the roof match those seen in the panoramic photo. Here's a detail from the above panoramic photo:

In 1909, the Browns played a dozen games against the Tigers in Detroit: April 30, May 1, June 22, June 23, June 24, June 25, June 26, September 5, a doubleheader on September 6, September 13 and September 14.

According to The Sporting Life of May 8, 1909, the April 30 game between Detroit and St. Louis was "played on a damp field in very cold weather." Not only does the field not look particularly damp, many of the fans have removed their jackets. This date is highly unlikely.

The next day's game can also be eliminated, as the same paper stated:

It was bitterly cold, a high wind blew and the umpires stopped the game in the fourth and again in the sixth because of blinding snowstorms that interrupted play.The next series of games took place in June and these five dates are all much more likely.

The early September series is a possibility, though Criger did not play in the field during the first game of the doubleheader on September 6, so we can eliminate that game from the running.

Finally, the mid-September pair of contests are out, as Criger did not play in either game.

We are left with the following possible dates: June 22, June 23, June 24, June 25, June 26, September 5, and the second game between the Browns and Tigers played on September 6.

The photo is wonderful, not just because it captures a great bit of action at the plate, but it encapsulates the turbulent history between Criger and Cobb. According to The Sporting Life of March 27, 1909:

Catcher Criger, of the Browns, [was] quoted as saying that Ty Cobb is a bone-headed base-runner, and that he can outguess Tyrus.Two months later, in the May 22 issue of The Sporting Life, Cobb was reported as saying:

I never knock a ball player. Yes, Criger is a good catcher, but I don't believe he's playing the game he put up last year. I'll say this much, though, that I think he and Cy Morgan tried to put me out of business last year over in Boston. You know Morgan throws a vicious ball. He aimed one at my head and if I hadn't fallen it would have killed me.In the biography titled Ty Cobb, Charles Alexander summarized the Cobb-Criger rivalry of 1909:

Just as the Browns left Dallas (their spring training site) and the Tigers came in, the local newspapers quoted Criger as bragging that Cobb had never given him much trouble and that "I've got his 'goat,' and I've got the rest of that Tiger bunch, too." Criger went on to say that in past seasons, when Cobb got up after dodging close pitches called by Criger, "the fight was all out of him."I tried to track down microfilm of The Detroit News Tribune on inter-library loan, but unfortunately I struck out. So I contacted my good friend, Peter Morris, who lives in Michigan, in hopes that he might be able to do some quick sleuthing. It also doesn't hurt that Peter is simply unsurpassed when it comes to baseball research.

Before Criger could get out of Dallas, Cobb hunted him up to promise that he would steal on Criger the first time he got on base against the Browns that year. That he did, when the Browns came into Bennett Park on April 30. It would make a good story if Cobb had actually run wild on Criger everytime Detroit and St. Louis met for the rest of the season, as Cobb later claimed in his autobiography. Yet besides Cobb's confusion in chronology, so that he had Criger in 1909 still catching Cy Young for Boston, the fact is that Criger generally held his own against Cobb and the rest of the Tigers on the few occasions when he played against Detroit that year. Cobb never successively stole second, third, and home on Criger, as he maintained. On May 1 he did clearly show up the veteran catcher by taking second after hitting into a fielder's choice, as Criger held the ball at homeplate; and toward the end of the season he stole second and third in succession on Criger. But on June 24, Criger pegged him out twice in a row, and later that day Criger took Cobb's spikes on his unguarded shins to tag out the Georgian as he tried to score from third on a grounder to shortstop Bobby Wallace. Criger stamped the pain off, stuck a gauze pad on his wound, and stayed in.

Indeed, Peter came through with flying colors, tracking down the photo in the Sunday, June 27, 1909 edition of The Detroit News Tribune. The photo, taken the previous day, was preceded by the following title:

COBB SPRINTED HARD TO MAKE FOUR BASES ON

HIS DRIVE, BUT THE BALL BEAT HIM TO THE PLATE

The Camera Shutter Snapped as the Georgian Slid to the Plate and the Veteran, Lou Criger, Tagged Him. The Ball Hit the Right Field Bleachers, But Bounded Back Into Hartzell's Hands, and a Quick Relay Resulted in the Georgian's Retirement at Home.Umpiring behind the plate that day was Billy Evans, seen running in on the play at right.

The story of the game was a mistake by Criger (likely caused by Cobb's tactics) that cost the Browns the game. Here's the synopsis of the play as reported by The Washington Post on June 27:

Catcher Lou Criger made the champion bonehead play of major league history today, and through it lost a chance for an almost sure triple play and the cutting off of four Detroit runs. Incidentally, Detroit for a moment practically had four men on bases, paradoxical as the statement may seem. Crawford, Cobb, and Rossman had got on in order, with none out and O'Leary next up. He hit rather weakly to Jones, who pegged to Criger to force Crawford.Still, Criger managed to retire Cobb on his attempt for an inside-the-park home run, as captured in this beautiful photo of the play at the plate of June 26, 1909.

The play was so easy that Crawford only trotted in, expecting a sure out. But Cobb upset things. He commences to yell to Rossman and O'Leary to come on, and apparently got to Criger's goat, for Criger, without touching the plate, pegged back to Jones. Jones kept his head and shot the ball back to Criger, O'Leary being safe at first in the meantime.

Crawford stopped stockstill and nobody was out and four on, while Criger just stood and looked. Finally, Crawford made a dash for the plate and Criger touched him. On the original toss home, if he had stepped on the plate and thrown to third he surely would have got Cobb and probably Rossman too, and there would have been three out and no runs.