One of the most famous baseball quotes of all time is attributed to famed sportswriter Red Smith. There have been various versions used by Smith, but it essentially goes like this:

Ninety feet between bases is perhaps as close as man has ever come to perfection.The problem is that the distance between the bases isn't 90 feet at all. What is the 90-foot distance all about? Well, the key is that a 90-foot square (generally called a "diamond") is used to help lay out the bases on the infield. But the bases aren't all the same size (home is a very special shape) and they are not all placed in similar locations relative to the corners of the 90-foot diamond.

In a prior blog entry (which I encourage the reader to review), I discuss the little-known fact that the rules of baseball require that home, first, and third bases each nestle neatly in their respective corners of the 90-foot diamond, but second base is centered on its corner of the diamond.

Here's a diagram (not drawn to scale) from the official rule book that shows the situation:

So, while the infield is laid out on a 90-foot diamond, the shortest distance between consecutive bases is clearly less than 90 feet.

So what are the distances between bases? To answer this question we first need to first define these distances as the shortest length between one base and the next.

It seems that we have four distances to determine: home to first, first to second, second to third, and third to home. However, the layout of the bases is reflectively symmetrical. That is, one can draw a line running through the center of home base and through the center of second base such that the left side and right side of the infield are mirror images of one another. Thus, the distance between home and first is identical to the distance between third and home. And the distance between first and second is the same as the distance between second and third. So, there are actually only two distances to calculate, not four.

Let's calculate two distances that are often covered by base stealers: first to second and third to home. Obviously the dynamics of stealing second base are quite different from those of stealing home, but still it should be interesting to compare the actual distances covered.

The easiest distance to calculate is that between first and second base. The shortest distance between first and second is represented by the double-headed red arrow in the diagram below, while the double-headed blue arrow is identical in length to one side of the 90-foot diamond:

All one needs to know to determine the length of the double-headed red arrow is the size of first and second base (which, of course, is also the size of third base). Each base is a square, 15 inches on a side. So, we need to subtract the full length of first base and half the length of second base (remember it is centered on its corner of the diamond) from the 90 foot double-headed blue arrow to determine the length of the double-headed red arrow:

distance between first and second = 90 feet - 15 inches - 7.5 inches

distance between first and second = 90 feet - 22.5 inches

distance between first and second = 90 feet - 1.875 feet

distance between first and second = 88.125 feet or 88 feet 1.5 inches

Now we are left with the more difficult calculation: the distance between third and home. The problem is the rather strange shape of home base. First, a bit of an aside to explain why it is that we have such an awkward-looking, five-sided home base.

For a number of years prior to the turn of the century, home base was a square, 12 inches to a side. Like first and third, home was nestled snugly in its corner of the diamond. However, in 1900 home plate was changed to its modern shape. Spalding's Official Base Ball Guide of 1900 explained the reasons behind the change:

With the plate placed in accordance with the form of the diamond field, that is, with its corner facing the pitcher instead of one of its sides, a width of 17 inches was presented for the pitcher to throw the ball over instead of 12 inches, the width of each side of the base. But this left the pitcher handicapped by having to "cut the corners" as it is called, besides which the umpire, in judging called balls and strikes, found it difficult to judge the "cut the corner" balls. To obviate this difficulty, the Committee [of Rules], while keeping the square plate in its old place—touching the lines of the diamond on two of its sides—gave it a new form in its fronting the pitcher, by making the front square with its width of 17 inches, the same as from corner to corner, from foul line to foul line. The change made is undoubtedly an advantage alike to the pitcher and umpire, as it enables the pitcher to see the width of base he has to throw the ball over better than before, and the umpire can judge called balls and strikes with less difficulty.

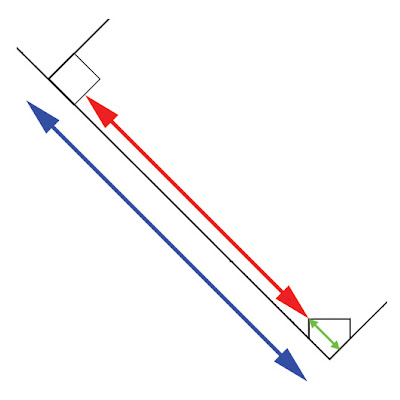

Now back to the calculation. In the diagram below, the shortest distance between third and home is represented by the double-headed red arrow. Note that this double-headed arrow runs from the home-base side of third to the closest corner of home plate. As in the above diagram, the length of the double-headed blue arrow is 90 feet.

Now for the hard part. What is the distance represented be the double-headed green arrow? The following diagram should help us determine that important information:

Distance C is what we are trying to determine. But C is the sum of distance A and B. To calculate A and B, we simply need to apply the Pythagorean Theorem. Remember that? Here's a refresher: In a right-angled triangle, the square of the hypotenuse (the longest side of the triangle) is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides.

By the way, have you ever noticed that near the end of The Wizard of Oz, the Scarecrow, in an effort to show off his new honorary degree of Th.D. (Dr. of Thinkology), incorrectly states the Theorem? His butchered version is "The sum of the square roots of any two sides of an isosceles triangle is equal to the square root of the remaining side." Check it out:

But we've stalled long enough. Back to the math. First let's calculate distance A:

A2 + A2 = (17 inches)2

2A2 = 289 inches2

A2 = 144.5 inches2

A = 12.02 inches

Now distance B:

B2 + B2 = (8.5 inches)2

2B2 = 72.25 inches2

B2 = 36.125 inches2

B = 6.01 inches

And so the double-headed green arrow (C) can now be calculated:

C = A + B

C = 12.02 inches + 6.01 inches

C = 18.03 inches

All that is left to do is to subtract the full length of third base (15 inches) and distance C (18.03 inches) from the 90 foot double-headed blue arrow to determine the length of the double-headed red arrow:

distance between third and home = 90 feet - 15 inches - 18.03 inches

distance between third and home = 90 feet - 33.03 inches

distance between third and home = 90 feet - 2.7525 feet

distance between third and home = 87.2475 feet or 87 feet 2.97 inches

Finally, let's compare the two distances between bases:

distance between first and second = 88.125 feet or 88 feet 1.5 inches

distance between third and home = 87.2475 feet or 87 feet 2.97 inches

difference = 0.8775 feet or 10.53 inches

And so we have our answer. Indeed, the distance between bases is very different. In fact, the distance between third and home is over 10½ inches shorter than the distance between first and second.

Sorry, Mr. Smith.