Back in October of 2009, New York Times reporter John Branch broke a story about some newly discovered footage of Babe Ruth. The "never-before-seen" film was found in a collection of home movies belonging to an unnamed individual in New Hampshire and ultimately ended up at Major League Baseball's Film and Video Archive. The folks there suspected that the footage dated from 1928 and, according to archivist Frank Caputo, guessed that "it could be a world series game, could be opening day, maybe a holiday, July fourth?" But, as noted in a video accompanying the Times article, "the archivists are still trying to pin down the exact date of the footage."

Soon after the story came out, I decided to take a crack at solving the mystery.

Of course, it was simple to confirm that the location seen in the footage was Yankee Stadium. Not only do shots showing its structure match perfectly to the well-known stadium, but the Yanks are wearing their familiar pinstripes. That part was a piece of cake.

Next, I needed to establish the correct year of the photograph. Outfield advertisements can often be helpful in dating baseball images. They generally change every season (sometimes multiple times within a season) and can act as chronological "finger prints" that are uniquely associated with a particular year. (Outfield advertisements at New York's Polo Grounds were instrumental in solving a mystery in my blog titled "Take Me Out to the

Here is a frame from the new footage showing some of the outfield advertisements beyond the left field bleachers.

Alas, the sun is shining brightly on the walls, washing out many of the distinctive graphics. Still, take a look at the picture below, taken during Game Three of the 1928 World Series and published the following day in the Hartford Courant. While the quality of this halftone image is not great, careful examination shows that the outfield advertisements match those seen in the still from the footage:

While this comparison was helpful, I hoped to find a higher quality photo that would show the exact same advertisements as seen in the footage. I turned my eyes to this magnificent photograph from the collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum:

The panoramic image, shot by the Cosmo Foto Service, is actually a composite of three separate photographs, each "seamed" together to make a single, large-format picture. The process is less elegant than the stunning images made by special panoramic cameras (see my blog titled "Nix Flicks Sticks in Box for Sox in Rox"), but it is still an effective way to create a dramatic print.

According to the caption written contemporaneously on the front of the photograph, the image was taken at the 1928 World Series between the Yankees and the Cardinals. Since the outfield ads matched those seen in both the Hartford Courant and the footage, my initial reaction was that the panorama confirmed the year as 1928. But after a closer look, I began to worry ... not about the year, but about the claim that it pictured action from the World Series.

An article in the Washington Post published the day after the first World Series game at Yankee Stadium that season stated that "the grand stand tiers were bedecked in bright bunting and the national colors in much more profusion than ever before." But the panorama showed the famed park devoid of the traditional decorative bunting.

Furthermore, when I examined the player closest to the camera, the right fielder, I saw that he was wearing a uniform inconsistent with what the Yankees or the Cardinals wore during the 1928 World Series:

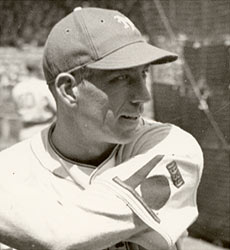

Note that the player's cap, pants and jersey are light-colored and his stockings are dark-colored with two white stripes. Now take a look at this photograph of Cardinals manager Bill McKechnie and Yankees skipper Miller Huggins posing at Yankee Stadium during the World Series:

New York Yankees History

Huggins and the Yankees wore pinstriped uniforms with dark caps and dark stockings ... quite different from the outfit worn by the left fielder. McKechnie and the Cardinals also wore pinstripes, and their stockings are nearly the opposite of those worn by the left fielder: light colored with multiple dark stripes.

In short, the player in left field was neither a Yankee nor a Cardinal, and the park was not decked out for an occasion such as the World Series. And yet the shot is certainly from 1928, as the outfield ads matched those seen in the 1928 Hartford Courant photo. What was the scoop?

In 1928 only one major league club wore road uniforms consistent with that worn by the right fielder: light-colored uniform and cap, and dark-colored stockings with a pair of white stripes. That club was the Philadelphia Athletics. Here are drawings of the uniform worn by the 1928 Athletics from the National Baseball Hall of Fame's online exhibit, Dressed to the Nines:

For this reason, it seemed likely that the team in the field as seen in the panorama was the Athletics. Embracing this theory, I set out to see if I could come up with an exact date for the image.

The Athletics played 11 games at Yankee Stadium in 1928. Checking attendance records for each of these games, I found that only one date attracted the astounding crowd seen in the panoramic: a doubleheader played on September 9. On that day a record 85,625 fans packed Yankee Stadium. All signs point to the panorama capturing the scene at Yankee Stadium that very day.

Why did so many fans attend that game? Well, first of all, it was a Sunday doubleheader. And secondly, there was the very real feeling that the Sunday twin-bill (along with the subsequent two games of the four-game series) would have a major impact on just which club would advance to the post-season. The A's entered the day with a half-game lead over the Yankees, but after losing both games of the doubleheader and splitting the last two contests, Philadelphia left the Bronx trailing by 1.5 games. As the Yanks went 10-5 over their remaining 15 games and the A's posted an 8-5 mark in their final contests, one could argue that the four-game set was indeed the difference-maker in the pennant chase.

Taking another look at the mislabeled panoramic, I noted that the shadows were quite short. Thus, the photographs making up the panoramic image were assuredly taken early during the first game of the doubleheader. The second game can also be eliminated as a possibility since lefty Rube Walberg pitched the first 6.2 innings of that contest and the pitcher in the panoramic is right-handed:

With the date and game nailed down, a look at the box score revealed just who was in the field for the A's. On the mound was Jack Quinn who, at 45 years of age, was the oldest player in big league baseball. Catching the veteran moundsman was Mickey Cochrane, who ultimately earned the Most Valuable Player Award that season. Around the infield was Jimmie Foxx at first, Max Bishop at second, Jimmy Dykes at third, and Joe Boley at short. And the outfield featured Al Simmons in left, Mule Haas in center, and Bing Miller (whose stockings were so helpful in researching the photo) in right.

Just why the panorama was misidentified is not known, but I suspect that the folks selling the picture figured it would sell better if they passed it off as a World Series game, instead of a regular season contest.

Having gotten significantly sidetracked clearing up the misinformation written on the front of the panorama, I returned my attention to the newly discovered footage and the parade of batters captured on film.

Early in the footage, a left-handed batter is seen swinging and running to first. The stride and follow-through is unmistakably that of Yankees legend, Lou Gehrig:

The footage then quickly cuts to another unmistakable lefty at the plate: Babe Ruth. Interestingly, in this same scene, we see Gehrig (far left), who had failed to reach base just moments earlier, returning to the Yankees dugout:

However, the narrator of the New York Times video states that "Lou Gehrig waits on deck as the great Bambino strikes out."

Wait a second. How could Gehrig be waiting on deck when he just completed his at bat and is seen returning to the dugout? Here's how: That isn't Lou Gehrig waiting on deck!

Sure, throughout their careers together, Gehrig almost always followed Ruth in the batting order: Ruth batting third and Gehrig batting cleanup. But, in this particular footage, that just wasn't the case.

It's not clear who misidentified the on-deck batter, the folks at the New York Times or the folks at MLB Productions, but even though the quality of the video is rather poor, one can tell the on-deck batter is taller and leaner than Gehrig. More about that fellow in a moment.

At this point I had established that the action in the film took place at Yankee Stadium in 1928 and that Gehrig batted ahead of Ruth. A quick check at the always-useful retrosheet.org web site revealed that manager Miller Huggins flip-flopped Gehrig and Ruth in the batting order for a stretch of some four weeks near the end of the season: from August 25 (starting in the second game of the double-header) to September 20.

Here's what was reported in the New York Times the day after the of August 25 doubleheader:

After our boys, in the first game, had given one of the most terrible exhibitions ever seen of bad pitching puny hitting and general indolence, Miller James Huggins instituted the most drastic shake-up of the last several years.

What Miller James did to the batting order between games was nobody's business. He took it apart to see what made it tick and then threw the pieces together in a very careless manner.

The one and only Babe Ruth was dropped from third to fourth place. Henry Gehrig ascended from fourth to third, Joseph Dugan was made lead-off man, Combs fell to second and Mark Koenig landed with a sickening thud in sixth. To make matters unanimous Tony Lazzeri was benched and [Leo] Durocher played second base.

One of the few Yankees to be unaffected by the line-up reshuffling was the man who batted fifth: Bob Meusel. He remained in that spot during Huggins' late-season switcheroo. Indeed, that's the 6' 3" Meusel seen waiting on deck during Ruth's at bat in the footage, not the 6' 0" Gehrig. Here's another frame from the film, showing "Long Bob" Meusel (at left) leaning on his bat as Babe Ruth stands at home, clearly upset that he was called out on strikes:

At this point, I had made good progress with the footage, determining that it was shot sometime between August 25 and September 28, 1928. I next took a closer look at the opposing team's catcher. Here's a still from the footage:

We can determine the following about his uniform: the crown of his cap is light-colored and his stockings are dark-colored from knee to shoe, possibly with light-colored stripes. This combination of cap and stockings was worn by only one American League club on the road in 1928. That club was none other than the Philadelphia Athletics.

The Athletics played just four games at Yankee Stadium during the time-period noted above: the doubleheader of September 9, and games on September 11 and 12.

Hold on! Is it possible that the film footage was taken on the same day as the mislabeled panoramic picture? Certainly the massive crowd shown in the footage points to that date, but I wondered if there might be a way to tell for sure that they matched. Happily, I found a way.

I decided to overlay a still from the footage (below) on the panoramic picture. Both images show the crowd down the third base line.

Despite the fact that the cameras shot action from significantly different angles, I was able to align the images such that the gates at the bottom of stairways (see arrows) were aligned perfectly:

Note that some of the fans in the front row have draped clothing atop or over the railing. While the still from the footage is much blurrier than the photograph, I was able to match the shadows created by the clothing (see arrows). Take a look:

There's really no question about it. The footage and the panoramic picture were both shot at Yankee Stadium during the first game of a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Athletics on September 9, 1928. In fact, reviewing play-by-play of the game, the action captured in the film fits perfectly (and only) with what occurred in the bottom of the fourth inning. After Mark Koenig led off the frame with a single to left field, Gehrig popped out to second. Ruth then struck out, after which Meusel flied to center. No other sequence in the game matches what we see in the footage.

I found additional corroboration of these findings in a Boston Globe story published the day after the game:

When the Yankees came up again, Koenig snapped out a sprightly single to left but Gehrig popped out to Bishop. Ruth fanned again and Meusel flied out to Haas. The canny Quinn pitched low and outside to the Babe, to prevent a rightfield catastrophe. The Babe was considerably peeved when the third strike was called and threw his bat toward the stands, narrowly missing [New York City mayor] Jimmy Walker.

To bad the footage didn't stay on Ruth a bit longer so we could witness his bat throwing tantrum. Oh, well. At least now the mystery has been solved.

By the way, back in 2009, Keith Olbermann also came to the conclusion that the footage came from the September 9, 1928, doubleheader. Both of our work was featured in John Branch's follow-up New York Times article.

Finally, if you're interested in obtaining a copy of the rare 1928 panoramic image, don't hesitate to contact John Horne in the Hall of Fame's Photo Department (jhorne@baseballhall.org).