In 1912, the Collins McCarthy Candy Company issued its second series of Zee-Nut baseball cards. That same year, the confectioners produced another series of cards, these packaged with a candy called Home Run Kisses. With the release of these two sets, the San Francisco-based company unwittingly documented an important, but generally overlooked moment in baseball history. More about that in a moment, but first a bit about the candies.

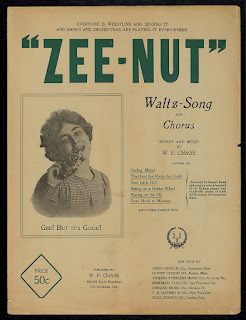

Zee-Nut

Introduced in California in 1908 and invented by William P. Chase, Zee-Nut candy was something like a coconut version of Cracker Jack, the popular candy that was first introduced a dozen years earlier. Zee-Nut consisted of popcorn, peanuts, and coconut, all mixed together with a sugary syrup. Chase (who later sold out to Collins McCarthy) worked hard to market the candy, and in March of 1908 it quite literally exploded on the scene:

Advertisement in the Los Angeles Herald of March 1, 1908

As noted in the Los Angeles Herald of March 1, 1908, “THE HERALD will ‘explode’ a bomb up in the air about a thousand feet above the W.P. CHASE Zee-Nut Factory, 420-422 South Broadway, and as it explodes 1030 coupons will be set loose and fall to the street below. Each of these coupons will be good for free presents.” The presents listed included silver dollars, boxes of candy, fountain pens, watch fobs, and, of course, packages of Zee-Nut.

There were even coupons for sheet music of the “Zee-Nut Waltz-Song and Chorus,” with music and lyrics by Chase, and published by Chase. In short, William Chase was all in on promoting his candy.

In 1911, Collins McCarthy enticed kids to purchase Zee-Nut by inserting pictures of Pacific Coast League players in packages of their candy. Apparently the scheme worked well, because they continued the baseball card promotion the following year ... and for many years afterward, their last set being issued in the late 1930s.

The 1912 Zee-Nut cards (each 2⅛" × 4" in size) once again featured pictures of PCL minor leaguers. The complete set numbered 158 cards in total (some sources say 159) and is known to modern-day collectors by the designation E136.

Advertisement in the San Francisco Call of May 11, 1912

Highlights from this set include:

A card of Sacramento pitcher John Williams, who two years later played four games with the Detroit Tigers to earn the distinction of being the first native of Hawaii to play in the major leagues.

A card of 18-year-old Joe Gedeon, who spent the 1912 season with the San Francisco Seals, batting .263 and stealing 26 bases. Though he eventually made the big leagues, Gedeon’s mark in baseball history came about off the field, when he admitted in the fall of 1920 that a year earlier he had learned from White Sox shortstop and insider Swede Risberg that the 1919 World Series was “fixed.” Gedeon, then the starting second baseman for the St. Louis Browns, won $600 betting against Chicago. On November 3, 1921, Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis permanently banned Gedeon from the game.

And perhaps you have heard of Gedeon’s nephew, Elmer Gedeon, who had a “cup of coffee” with the Washington Senators in 1939, taking part in five games with the club in his brief major league career. On April 20, 1944, Gedeon’s B-26 Marauder bomber was shot down over France. Of the over 500 major leaguers who served during World War II, only Elmer Gedeon and Harry O’Neill, who played a single game with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1939, were killed during action.

Home Run Kisses

Hardly anything is known about Home Run Kisses, a confection that was apparently something like salt-water taffy. Introduced by Collins McCarthy in 1912, each five-cent package of the candy came with a PCL player card similar in size to the Zee-Nuts, though the set numbered just 90 cards. Highlights include:An early card of future Hall of Fame shortstop Dave Bancroft when he was a member of the Portland Beavers.

A card of Los Angeles Angels outfielder Heinie Heitmuller, who captured the 1912 PCL batting championship with a .335 mark, but contracted typhoid fever and passed away weeks before the season ended.

But the truly wonderful thing about both the 1912 Zee-Nut and Home Run Kisses cards is that many of the pictures showed ballplayers wearing numbers on their left sleeves. Here are just a few examples that clearly shows the numbers:

What gives?

At their annual winter baseball meeting in January of 1912, the directors of the Pacific Coast League adopted a league-wide rule mandating that all six clubs add numbers to the sleeves of their uniforms, both home and abroad.

Akron Beacon Journal, January 16, 1912

Early Uniform Numbering

The idea of numbering players had been tried by various clubs, both in and out of Organized Baseball, years prior to the PCL’s 1912 rule, but never before had it been agreed upon by an entire league.Most people credit the 1929 Yankees as the first baseball club to place uniform numbers on the backs of their jerseys, but this was simply not the case. In fact, the Yankees weren’t even the first club to don numbers that season. That distinction goes to the Cleveland Indians, who beat the Yanks to the punch because the New Yorkers were rained out on Opening Day, while Cleveland remained dry that same day, April 16, 1929. A photo ran in the Cleveland Plain Dealer the next day, showing Indians catcher Luke Sewell wearing uniform number 8 in that historic game:

Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 17, 1929

While the 1929 Indians were the first major league baseball club to wear numbers on their backs, they weren’t the first in the big leagues to wear numbers somewhere on their uniform. That distinction goes to these same Indians, but 13 years earlier. On June 26, 1916, Cleveland took the field wearing numbers on their sleeves. As noted by the Zanesville (OH) Times Record the next day, “The numbers corresponded to similar numbers set opposite the players’ names on the score cards, so that all fans in the stands might easily identify the members of the home club.”

This photo of the Indians with their short-lived numbers ran in the 1917 Spalding Guide. Note: Don’t confuse the numbers on the sleeves with the numbers that were hand-drawn on the photo to help identify the players.

Cleveland’s experiment in 1916 lasted just a short while (as did a brief revival of the scheme by the 1923 St. Louis Cardinals), but the PCL’s uniform numbers of 1912 lasted the entire season. Prior to the 1913 campaign, however, the league dropped the sleeve-numbering rule. Some league officials wanted to keep the numbers, but most were against continuing the practice, complaining that the numerals were too small to be easily seen by fans in the stands and, as reported by the Portland (OR) Oregonian, “numbering the men did not help the sale of score cards, as was expected.”

One additional note: A few cards from the 1913 Zee-Nut set featured photos taken of PCL players in 1912, as they can be seen with numbers on their left sleeves. Here are a few examples of those 1913 cards:

Thanks to the Collins McCarthy company and their 1912 Zee-Nut and Home Run Kisses baseball cards, today we have a visual record of this important moment in the history of baseball uniforms.

List of 1912 Pacific Coast League Uniform Numbers

While there is no complete list of each PCL club’s uniform numbers from 1912, an article in the Oregon Daily Journal of March 27, 1912, did list the numbers initially assigned to members of the Portland Beavers. Combining this information with a few notes from other contemporary newspaper accounts, closely examining some team photos, and scouring numerous Zee-Nut and Home Run Kisses baseball cards from 1912 (as well as a few from 1913) allows us to create a partial list of 1912 PCL uniform numbers.

Los Angeles

1 - Ivan Howard

1? - Joe Berger

1 or 2? - John Core

4 - Heinie Heitmuller

5 - Babe Driscoll

8 - Hugh Smith

9 - Walter Boles

18 - John Halla

20 - Charlie Chech

22 - Jack Flater

23 - Elmer Gober

Oakland

4 - Bud Sharpe

6 - Al Cook

7 - Gus Hetling

13 - Harry Ables

15? - Tyler Christian

16 - Bill Malarkey

21? - Cy Parkin

Portland

1 - Bill Rapps

2 - Jack Gilligan

3 - Dave Bancroft

4 - Dan Howley

5 - Bill Rodgers

6 - Walt Doan

7 - Bill Lindsay

8 - Art Kruger

9 - Chet Chadbourne

10 - William Temple

11 - Spec Harkness

12 - Ben Henderson

14 - Fred Lamlein

15 - Ward McDowell

16 - Heinie Steiger

17 - Mickey LaLonge

18 - Elmer Koestner

18 - Leo Girot

Sacramento

8? - Al Hiester

San Francisco

1 - Jesse Baker

1 - Willard Meikle

2 and 7 - Claude Berry

2 - Harry McArdle

4 - Chick Hartley

7 - Walter Schmidt

14 - Otto McIvor

17 - Kid Mohler

18? - Watt Powell

Vernon

1 - Walter Carlisle

2 - John Kane

4 - Ham Patterson

6 - George Stinson

7 - Franz Hosp

7? - John Raleigh

8 - Lou Litschi

11 - Wallace Hogan

12 - Drummond Brown

19 - Dolly Gray

22 - Sam Agnew

4-12-1912 SF Examiner has a picture of Oakland Zacher batting with SF Berry or Schmidt catching (#7). Zacher #10. Says it is Zacher hitting a HR which was in the 2nd inning which would be Berry catching, but possibly could be Schmidt and pic of wrong AB used

ReplyDeleteThanks, Leman! I'm pretty sure that the catcher is indeed Claude Berry, as he isn't wearing shin guards ... unusual by that time. The SF Chronicle of April 3, 1912, stated that Berry "went behind the log yesterday without his shin guards, and he may do without them all season, as he claims that they slow up a catcher." So, I'll list him as both 2 and 7.

ReplyDeletep.s. I believe you meant to date the Examiner picture as 4-7-1912, not 4-12-1912.