Keith Olbermann recently posted a fine blog entry in which he unveiled some wonderful photos from the 1894 Temple Cup Series, a post-season match-up between the National League pennant-winning Baltimore Orioles and the second place New York Giants. In this early incarnation of the World Series, New York won the best-of-seven series in four straight games to become World Champions.

Like Keith, I was unfamiliar with the photos, so I thought I'd research them. While I didn't make much headway on that front, I did uncover another new facet to the Series: accusations of the use of performance-enhancing drugs!

The November 26, 1894 issue of The Medicine Age: A Semi-Monthly Review of Medicine published an article titled Facilis Est Descensus Averni (Latin for "the descent to hell is easy"). The article, available at Google Books, quoted heavily from the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat of November 12th. I don't have access to the original Globe-Democrat article, but here is how it was quoted in The Medicine Age:

This final paragraph is astonishingly prescient, foreshadowing issues facing Major League Baseball over a century later.A BASE-BALL ROW.

… A man who traveled with the Giants during the last half of their present season, … equally a friend of the star pitcher of the Giants and … the Orioles, is responsible for the current row. A few days after the final Temple Cup game had been won by the Giants, a party made up of ball-players and actors were seated around a table at a New York club discussing the recent event, when the man above referred to said: "Boys, you are all wrong. I know how these games were won. Two of the Giants made the telling plays in the Temple Cup games, just as they did two weeks ago in Chicago. … The first game that day was won by a terrific hit over the left-field fence in the seventh inning. In the second game a long hit to right in the fourth inning won out. I could follow every game played and show you how at a critical point one or the other of these two men rose to the occasion. You wish to know why these two particular men, and how they did it? This is the solution." The speaker held between his finger and thumb a diminutive three-cornered blue phial. He continued: "May be, you all do not know that R—— … is a pretty good doctor. … When we got to Washington he asked W—— and myself to go with him one morning to call on a doctor who is supposed to be thoroughly up in Isopathy. The visit was most interesting, and when we left, R—— and W—— had promised to test the virtue of the elixir contained in these little bottles. The opportunity occurred in Chicago September 18th. The score was 1 to 1, each team having tallied in the sixth. R—— was now up, but before taking the bat I saw him pass something to his mouth and then look up for quite two minutes. His eyes brightened and the veins across his temples and the arteries down his neck knotted like cords as he stood at the plate. … R—— met the ball … and he put his 230 pounds in the lunge he made; … the ball was bound for the outer world, and would not have stopped if the fence had been twice as high. Three runs were tallied, and, as it proved, they were just about the number needed.

"As R—— dropped down on the players' bench beside me all breathless from the home run, he managed to pant, 'Charlie, the elixir is a "Jimdandy."' R—— did not play in the second game that day, but just before W—— went to the bat in that critical fourth inning he gave him a dose from the blue phial. The effect was marvelous. W——'s strength seemed to be doubled and he whacked out that hot liner to right which saved the game to the Giants. … Those two boys have used it ever since, except in Pittsburg, when a new supply of the stuff failed to arrive. The Giants lost that game, but won the next day when the package arrived. They used the Washington physician's elixir in every Temple Cup game, and I tell you that is the secret of the Giants holding that trophy to-day. R—— and W—— will both tell you so."

… Anson of Chicago, hearing it, claimed that the effect of ——'s Cerebrine, the extract of the brain of ox, is to add immediate strength to the player, and thus place his opponent at a great disadvantage. … He sent copies of the protest to every club in the league.

From a small beginning a tempest has arisen, which bids fair to end only when the question shall have been decided as to the rights of players in regard to utilizing scientific methods for adding to their dynamic value during the progress of ball games.

The article disguises three names: those of two Giants players (R—— and W——) and the doctor (——), but a quick bit of digging reveals these individuals' identities.

As described in the article, the Giants did indeed face Chicago in a doubleheader on September 18, winning both games. The Washington Post of September 19 corroborated the Globe-Democrat story:

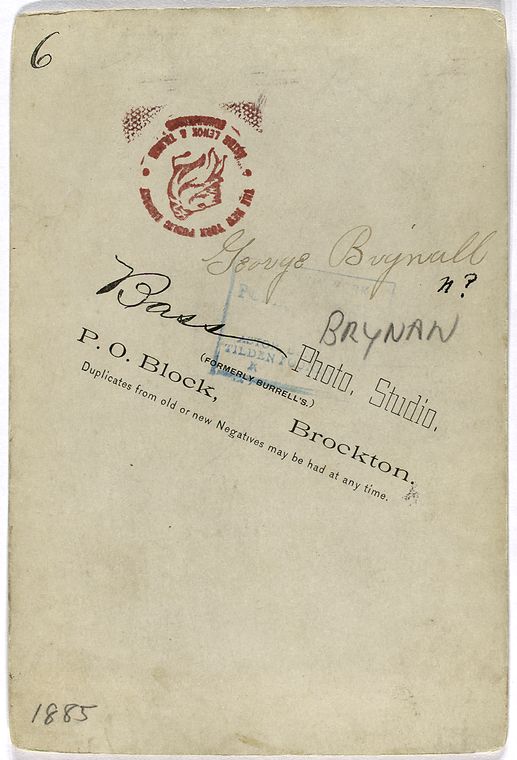

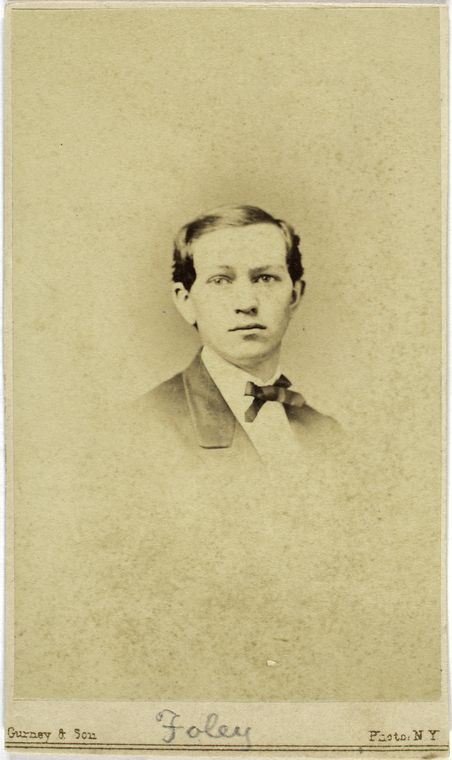

Clearly, R—— is none other than famed pitcher Amos Rusie. Indeed, he is the only player on the 1894 Giants roster whose last name begins with "R." Here is an 1895 Mayo Cut Plug (N300) tobacco card of Rusie (misspelled "Russie"):

Rusie won the first [game] by a home run hit over the left field fence in the seventh inning with two outs and two men on bases.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-bbc-0597f

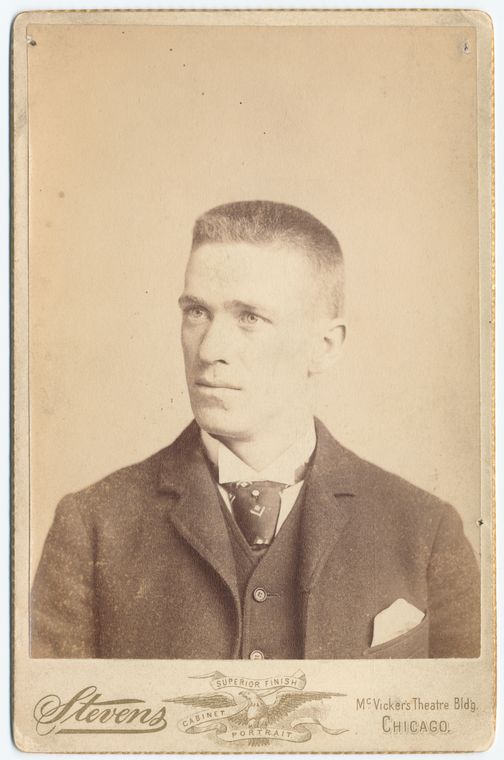

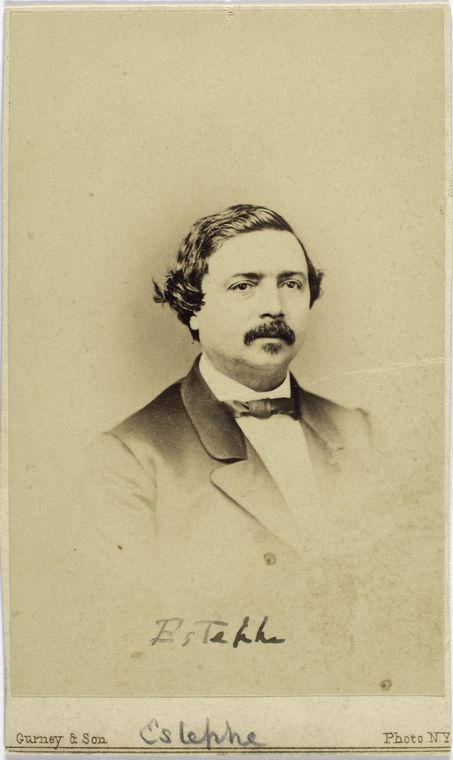

While three players on the club had a last name starting with "W" (John Ward, Parke Wilson and Huyler Westervelt), only Ward participated in the doubleheader. It was Ward whose "strength seemed to be doubled" and who "whacked out that hot liner to right" in the second game against Chicago. Here's Ward's baseball card from the same set as above:

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-bbc-0598f

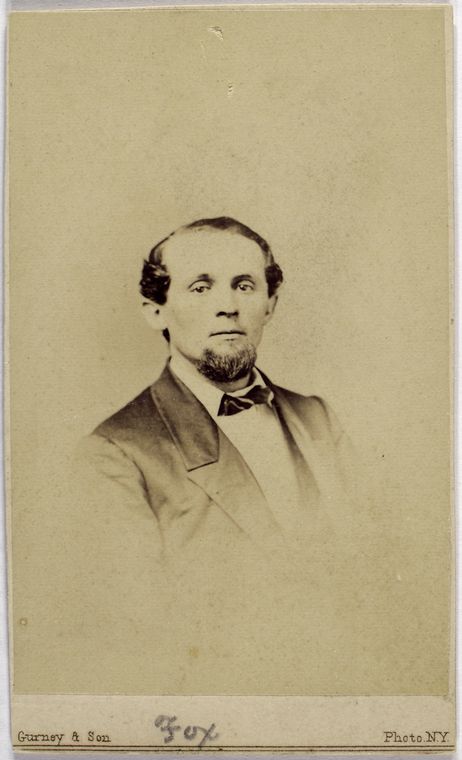

As for the Washington doctor, I suspect it was one William Alexander Hammond, pictured below. Hammond had been Surgeon General of the U.S. Army during much of the Civil War and a co-founder of the American Neurological Association. More to the point, by the 1890s the doctor was a major player in the world of isopathy, researching and writing extensively on the subject.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-cwpb-05202

Hammond was very familiar with the animal extract research undertaken years earlier by Dr. Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard. Apparently, one of these Brown-Séquard elixirs was used in the late 1880s by pitching great Pud Galvin. (More on that story can be found here.)

Under Hammond's supervision, the Columbia Chemical Company manufactured animal extracts such as Cerebrine, which the doctor both advocated and advertised. An ad published in the May 8, 1894 issue of The Washington Post was typical, stating that

In the March 10, 1894 issue of The Medicine Age, a letter to the editor described that "the preparation employed was put up in a triangular bottle holding two drachms, and obtained directly from the Columbia Chemical Company." And, in the September 26, 1893 issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) an article by Dr. John Harper Long of Northwestern University examined two of Hammond's extracts (Cerebrine and Medulline), noting that

… the physiological effects produced by a single dose of CEREBRINE are acceleration of the pulse with feeling of fullness and distention in the head, exhilaration of spirits, … [and] increase in muscular strength and endurance.

Both of these quotes match up well with the "three-cornered blue phial" described in the Globe-Democrat article.

… each small blue bottle was in a dark red pasteboard carton, labeled "Sterilized Solution of Cerebrine" and "Sterilized Solution of Medulline," with the name "William A. Hammond" in facsimile printed diagonally across it in red ink.

Baseball Researcher blog reader Matthew Namee sent along a wonderful article in which Hammond is extensively interviewed about his products. The reporter was favorably impressed:

As it turns out, the whole thing was quackery at its finest. Not only were the effects of Cerebrine called into question by the medical community, but it appears that what Hammond was selling to the public was not animal extract at all. In the JAMA article, Dr. Long ultimately concluded that "the preparations 'Cerebrine' and 'Medulline' contain nitroglycerin as their active ingredients."

Five drops, with an equal quantity of distilled water, injected under the skin in the ordinary way is the dose. In five or ten minutes the pulse begins to beat much stronger and fuller, and increases ten to twenty beats a minute. The face becomes slightly flushed and there is a feeling of distension in the head, sometimes accompanied by a headache.

… Still more remarkable is the effect upon muscular strength. In the experiment which the writer had the pleasure of witnessing, a large and strong man was asked to put up a dumb bell weighing forty-five pounds. He did it fourteen times with his right hand and eleven times with his left. … After an injection of the fluid he "put up" the dumb-bell forty-two times with his right arm and thirty-five times with his left, and did it easier than before.

And in the June 1894 issue of The National Medical Review, Professor Albert B. Prescott of the University of Michigan described tests he made of Cerebrine purchased from Hegeman and Company, a drugstore at 196 Broadway in New York. Like Dr. Long, Professor Prescott found that the bottles contained nothing more than nitroglycerin.

The professor then prepared his own batch of Cerebrine, following the procedure published by Dr. Hammond. A warning: Prescott's description of the experiment may be a bit disturbing to the faint of heart.

Were Rusie and Ward ingesting the "real" Cerebrine, as disturbingly described above? Or did they take the nitroglycerin substitute? In either case, was the potion they swallowed responsible for an increase in their on-field strength and ability?

I have macerated the brain of the ox and the contained blood in a mixture of equal parts of absolute alcohol, glycerin, and a saturated solution of boric acid in water, with frequent agitation and strong pressure, five months and twenty days, and have then made chemical examination of a portion of the product. The product, at this period of maceration, perfectly agrees in appearance every way with the ' cerebrine' which I obtained from Messrs. Hegeman & Co. last September. But the ' cerebrine ' of my preparation, under the directions published by Dr. Hammond, with the time of maceration just stated, does not contain a trace of nitro-glycerin.

An article titled "The Latest Medical Fad," published in the February 1894 issue of The American Journal of Politics, summarized the apparent contradiction between Hammond as a respected physician and Hammond the "snake oil" salesman:

To summarize: Assuming that the Globe-Democrat article is factual (which is by no means a certainty), over a number weeks near the end of the season and into the post-season of 1894, John Ward and Amos Rusie ingested an elixir that they thought would enhance their performance on the field. Whether it did or not, from actual physiological changes or a placebo effect, is not clear.

Dr. Hammond claims that cerebrine can strengthen the energy of the prize fighter, and the college crews, as well as cure disease, restore lost vigor, stimulate decaying intellect, renew the departing life. … If he is sincere he should be able to furnish some evidence of the truth of his claim.

Dr. Hammond is a scientist second to no physician in the United States. He offers us no clinical evidence. He shows us no cures. He points out no cases of old men made young again. He shows us only this farce of an athlete putting up a dumbbell, and a patent for his remedy.

… It is a pitiful —most pitiful exhibition of designing therapeutical insincerity. Dr. Hammond is a great man in the profession. He is a tower of professional grandeur and example. He is no man's intellectual inferior in the medical profession. In his specialty he has stood for years as the most imposing Colossus of them all. His cerebrine marks his fall.

It should be noted that the use of Cerebrine was neither illegal nor was it banned by Organized Baseball. Indeed, the Globe-Democrat article implies there was nothing to hide: "They used the Washington physician's elixir in every Temple Cup game. … R—— and W—— will both tell you so."

Still, should Ward and Rusie's use of Hammond's elixir constitute an early dalliance in the use of a performance-enhancing drug?